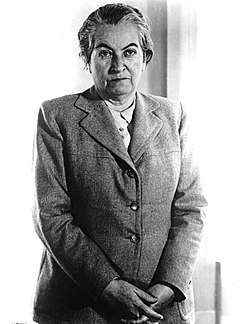

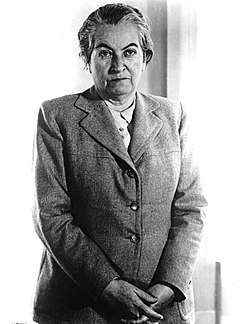

| Gabriela Mistral |

|

| Born | Lucila de María del Perpetuo Socorro Godoy Alcayaga

April 7, 1889

Vicuña, Chile. |

| Died | January 19, 1957 aoremovetag(aged 67)

Hempstead, New York |

| Occupation | Educator, Diplomat, Poet |

| Nationality | Chilean |

| Period | 1914–1957 |

| Notable award(s) | Nobel Prize in Literature

1945

|

|

| Signature |  |

Gabriela Mistral (1889–1957) was the pseudonym of Lucila de María del Perpetuo Socorro Godoy Alcayaga, a Chilean poet, educator, diplomat, and feminist who was the first Latin American to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, in 1945. Some central themes in her poems are nature, betrayal, love, a mother's love, sorrow and recovery, travel, and Latin American identity as formed from a mixture of Native American and European influences. Mistral herself was of Basque and Aymara descent.

Early life

Mistral was born in Vicuña, Chile, but was raised in the small Andean village of Montegrande, where she attended the Primary school taught by her older sister, Emelina Molina. She respected her sister greatly, despite the many financial problems that Emelina brought her, in later years. Her father, Juan Gerónimo Godoy Villanueva, was also a schoolteacher. He abandoned the family before she was three years old, and died, long since estranged from the family, in 1911. Throughout her early years she was never far from poverty. By age fifteen, she was supporting herself and her mother, Petronila Alcayaga, a seamstress, by working as a teacher's aide in the seaside town of Compañia Baja, near La Serena, Chile.

In 1904 Mistral published some early poems, such as Ensoñaciones ("Dreams"), Carta Íntima ("Intimate Letter") and Junto al Mar, in the local newspaper El Coquimbo: Diario Radical, and La Voz de Elqui using a range of pseudonyms and variations on her civil name.

Probably in about 1906, while working as a teacher, Mistral met Romelio Ureta, a railway worker, who killed himself in 1909. The profound effects of death were already in the poet's work; writing about his suicide led the poet to consider death and life more broadly than previous generations of Latin American poets. While Mistral had passionate friendships with various men and women, and these impacted her writings, she was secretive about her emotional life.

An important moment of formal recognition came on December 22, 1914, when Mistral was awarded first prize in a national literary contest Juegos Florales in Santiago, with the work Sonetos de la Muerte (Sonnets of Death). She had been using the pen name Gabriela Mistral since June 1908 for much of her writing. After winning the Juegos Florales she infrequently used her given name of Lucilla Godoy for her publications. She formed her pseudonym from the two of her favorite poets, Gabriele D'Annunzio and Frédéric Mistral or, as another story has it, from a composite of the Archangel Gabriel and the Mistral wind of Provence.

Career as an educator

Mistral's meteoric rise in Chile's national school system play out against the complex politics of Chile in the first two decades of the 20th century. In her adolescence, the need for teachers was so great, and the number of trained teachers was so small, especially in the rural areas, that anyone who was willing could find work as a teacher. Access to good schools was difficult, however, and the young woman lacked the political and social connections necessary to attend the Normal School: She was turned down, without explanation, in 1907. She later identified the obstacle to her entry as the school's chaplain, Father Ignacio Munizaga, who was aware of her publications in the local newspapers, her advocacy of liberalizing education and giving greater access to the schools to all social classes.

Although her formal education had ended by 1900, she was able to get work as a teacher thanks to her older sister, Emelina, who had likewise begun as a teacher's aide and was responsible for much of the poet's early education. The poet was able to rise from one post to another because of her publications in local and national newspapers and magazines. Her willingness to move was also a factor. Between the years 1906 and 1912 she had taught, successively, in three schools near La Serena, then in Barrancas, then Traiguen in 1910, in Antofagasta, Chile in the desert north, in 1911. By 1912 she had moved to work in a liceo, or high school, in Los Andes, where she stayed for six years and often visited Santiago. In 1918 Pedro Aguirre Cerda, then Minister of Education, and a future president of Chile, promoted her appointment to direct a liceo in Punta Arenas. She moved on to Temuco in 1920, then to Santiago, where in 1921, she defeated a candidate connected with the Radical Party, Josefina Dey del Castillo to be named director of Santiago's Liceo #6, the newest and most prestigious girls' school in Chile. Controversies over the nomination of Gabriela Mistral to the highly coveted post in Santiago were among the factors that made her decide to accept an invitation to work in Mexico in 1922, with that country's Minister of Education, José Vasconcelos. He had her join in the nation's plan to reform libraries and schools, to start a national education system. That year she published Desolación in New York, which further promoted the international acclaim she had already been receiving thanks to her journalism and public speaking. A year later she published Lecturas para Mujeres (Readings for Women), a text in prose and verse that celebrates Latin America from the broad, Americanist perspective developed in the wake of the Mexican Revolution.

Following almost two years in Mexico she traveled from Laredo, Texas to Washington D.C., where she addressed the Pan American Union, went on to New York, then toured Europe: In Madrid she published Ternura (Tenderness), a collection of lullabies and rondas written for an audience of children, parents, and other poets. In early 1925 she returned to Chile, where she formally retired from the nation's education system, and received a pension. It wasn't a moment too soon: The legislature had just agreed to the demands of the teachers union, headed by Mistral's lifelong rival, Amanda Labarca Hubertson, that only university-trained teachers should be given posts in the schools. The University of Chile had granted her the academic title of Spanish Professor in 1923, although her formal education ended before she was 12 years old. Her autodidacticism was remarkable, a testimony to the flourishing culture of newspapers, magazines, and books in provincial Chile, as well as to her personal determination and verbal genius.

International work and recognition

Awards and honors

Works

Each year links to its corresponding "[year] in poetry" or "[year] in literature} article:

See also

References

External links